You are now reading. This is probably not the first time you have read today and it likely will not be the last. Reading is a part of your life and it would not be at all difficult for you, if asked, to come up with a long list of the various functions reading serves in your life and the different contexts you use it in. We live in a world that is printed, painted, and neoned. Can you name a room that does not contain any words? For us, this is what literacy means: the ability to create and decode patterns of symbols in order to discern and convey meaning in the broadest sense. However, if we throw our attention to history we can still find writing carved, chiseled, and plastered throughout the densely occupied world, throughout the urban fabric.

By way of introduction, this is a blog about Roman public writing. Here we shall pursue a discussion of the uses, function, meaning, and interpretation of texts contextual to ancient public spaces. But this is meaningless as of yet. For if this leading post is to serve its function it must begin to present the questions and the groundwork for why this is a discussion worth having.

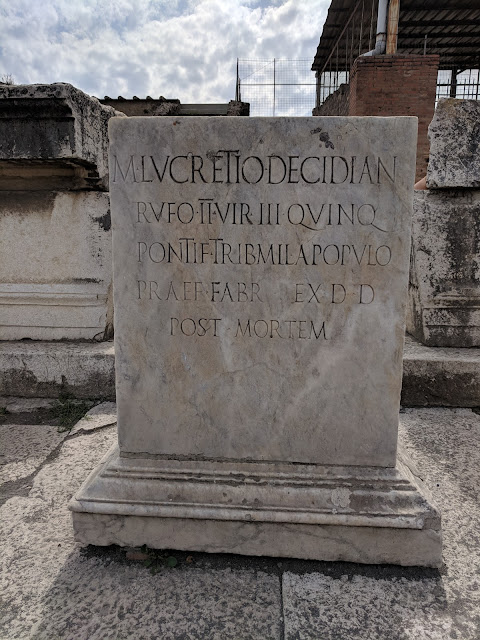

As Greg Woolf argues, the Roman world was "awash" with texts; buildings were inscribed, walls were painted, graffiti was etched, personal objects were engraved, statues were dedicated. The excavations at Pompeii alone have turned up over 11 000 pieces of writing. All of this, however, was the habitat of a people who were not, by and large, 'literate' by the standards we know today (the average member of the urban mob could not, for example, read or write equivalent to a modern high school graduate). Nevertheless, this was a society that displayed writing prominently and to whom writing was significant. Scholars like Woolf have gone to great lengths to describe to what degree and in what contexts different Romans could make meaning out of words; here theory will be applied.

Writings in Roman public spaces are not only meaningful in reference to their possible readers, but also concerning the spaces they occupy. Just as a title of a song or painting can provide the thematic context for understanding the piece, so too does an inscription contextualize a public space and, vice versa, a space give an autonomy and a voice to a text. In this way a text is not only an interaction between an author and an audience, where the former gives a message to the later, but the space is a key player. A text in a space exists with a degree of permanence; it is not reliant on an author or an audience, only the space it occupies. This lasting physicality of public writing, the fact that one could 'cite' the location of a non-oral document, gave these texts a importance of their own. Thus the space itself, the locus ipse, is a key player in the nature and significance of any public text.

The title of this blog, Ab Urbe Adspecta, consists of both a pun on the Roman author Livy's From the Founding of the City and a mission statement: this blog will seek to 'consider' and 'ponder' the Urbs Roma and significant nearby sights with the purpose of achieving, through many singular investigations, some understanding of how Roman public writing functioned, how it impacted its readers and authors, and how we can better understand our own relationship with the words around us.

Valete.

Bibliography:

Corbier, Mirelle. "Writing in Roman Public Space." In Written Space in the Latin West, 200 BC to AD 300, edited by Gareth Sears, Peter Keegan, and Ray Laurence. London: Bloomsbury, 2003.

Franklin, James L. jr. Pompeis Difficile Est: Studies in the Political Life of Imperial Pompeii. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Thomas, Rosalind. "Writing, Reading, Public and Private 'Literacies': Functional Literacy and Democratic Literacy in Greece." In Ancient Literacies: The Culture of Reading in Greece and Rome, edited by William A. Johnson and Holt N. Parker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Woolf, Greg. "Literacy or Literacies in Rome?" In Ancient Literacies: The Culture of Reading in Greece and Rome, edited by William A. Johnson and Holt N. Parker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

By way of introduction, this is a blog about Roman public writing. Here we shall pursue a discussion of the uses, function, meaning, and interpretation of texts contextual to ancient public spaces. But this is meaningless as of yet. For if this leading post is to serve its function it must begin to present the questions and the groundwork for why this is a discussion worth having.

All Photos here by Jack Hase at Pompeii, 2018.

As Greg Woolf argues, the Roman world was "awash" with texts; buildings were inscribed, walls were painted, graffiti was etched, personal objects were engraved, statues were dedicated. The excavations at Pompeii alone have turned up over 11 000 pieces of writing. All of this, however, was the habitat of a people who were not, by and large, 'literate' by the standards we know today (the average member of the urban mob could not, for example, read or write equivalent to a modern high school graduate). Nevertheless, this was a society that displayed writing prominently and to whom writing was significant. Scholars like Woolf have gone to great lengths to describe to what degree and in what contexts different Romans could make meaning out of words; here theory will be applied.

Writings in Roman public spaces are not only meaningful in reference to their possible readers, but also concerning the spaces they occupy. Just as a title of a song or painting can provide the thematic context for understanding the piece, so too does an inscription contextualize a public space and, vice versa, a space give an autonomy and a voice to a text. In this way a text is not only an interaction between an author and an audience, where the former gives a message to the later, but the space is a key player. A text in a space exists with a degree of permanence; it is not reliant on an author or an audience, only the space it occupies. This lasting physicality of public writing, the fact that one could 'cite' the location of a non-oral document, gave these texts a importance of their own. Thus the space itself, the locus ipse, is a key player in the nature and significance of any public text.

The title of this blog, Ab Urbe Adspecta, consists of both a pun on the Roman author Livy's From the Founding of the City and a mission statement: this blog will seek to 'consider' and 'ponder' the Urbs Roma and significant nearby sights with the purpose of achieving, through many singular investigations, some understanding of how Roman public writing functioned, how it impacted its readers and authors, and how we can better understand our own relationship with the words around us.

Valete.

Bibliography:

Corbier, Mirelle. "Writing in Roman Public Space." In Written Space in the Latin West, 200 BC to AD 300, edited by Gareth Sears, Peter Keegan, and Ray Laurence. London: Bloomsbury, 2003.

Franklin, James L. jr. Pompeis Difficile Est: Studies in the Political Life of Imperial Pompeii. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Thomas, Rosalind. "Writing, Reading, Public and Private 'Literacies': Functional Literacy and Democratic Literacy in Greece." In Ancient Literacies: The Culture of Reading in Greece and Rome, edited by William A. Johnson and Holt N. Parker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Woolf, Greg. "Literacy or Literacies in Rome?" In Ancient Literacies: The Culture of Reading in Greece and Rome, edited by William A. Johnson and Holt N. Parker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Comments

Post a Comment